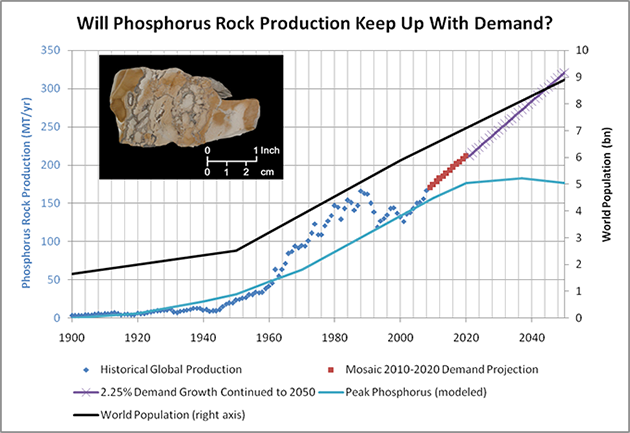

The U.S. — and North America as a whole — is becoming more and more dependent on the Middle East for a crucial resource. And it's not oil. An argument can be made that this resource is even more valuable than oil... because without it, mankind can't feed itself.

I'm talking about phosphate — the component in fertilizer essential for root and stem development in plants, and for which there is no agricultural substitute. Some 200 million metric tonnes are produced annually worldwide. Just about 70% of that comes from the Middle East and Northern Africa. For contrast, only about 40-50% of the world's oil comes from those regions.

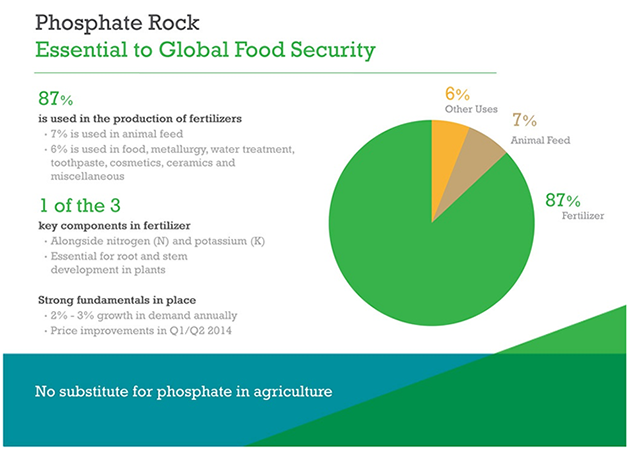

Of that 200 million tonnes produced annually, almost 90% of it goes toward the production of fertilizers. You know it as the P on the bags and bottles of fertilizers like Miracle-Gro and Scotts Turf Builder:

N = Nitrogen (growth)

P = Phosphate (root and stem development)

K = Potassium (drought resistance)

About 7% goes toward animal food. And the rest is used in various food and sundry industries like preservatives, cosmetics, soaps, and fungicides.

Now, not all phosphate makes it to market. Of the 200 million tonnes produced annually, 85% is integrated with downstream production. By that, I mean a major company like the $25 billion Potash Corp. (NYSE: POT) will use the phosphate it produces to make final products. Potash, for example, sells a dozen phosphate-based finished fertilizer products, and several more in the animal feed and industrial use spaces. So only about 15%, or 30 million tonnes, of the 200 million produced annually make it to market.

The 30 million tonnes that do make it to market go quick:

Western Europe imports 8 million tonnes per year (Mt/y)

India imports 7 Mt/y

U.S. imports 3 Mt/y

SE Asia imports 3 Mt/y

Latin America imports 2 Mt/y

They are all dependent on the Middle East and North Africa for that supply, especially Morocco, Syria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Tunisia, and Algeria. There aren't too many friendly or stable names on that list. Again, I'd argue the situation is worse than with oil. With so much supply coming from unstable places, rising population, and emerging markets requiring higher quality food and proteins (a chicken is corn with feathers on it, after all), demand for phosphate as well as prices are in an upward trajectory. Phosphate rock demand grows at 2-3% (4-6 Mt/y) per year.

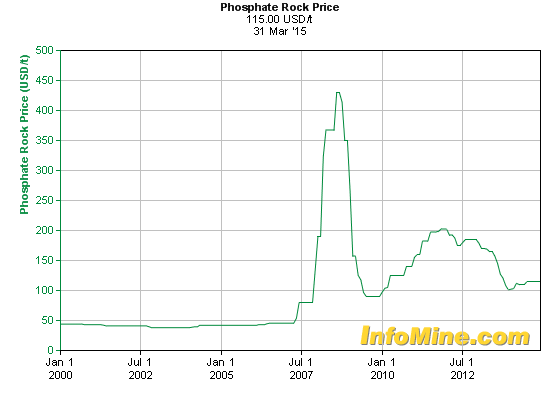

And prices have more than doubled in the years after the superspike in 2007/2008:

My Phosphate Is Not Your Phosphate

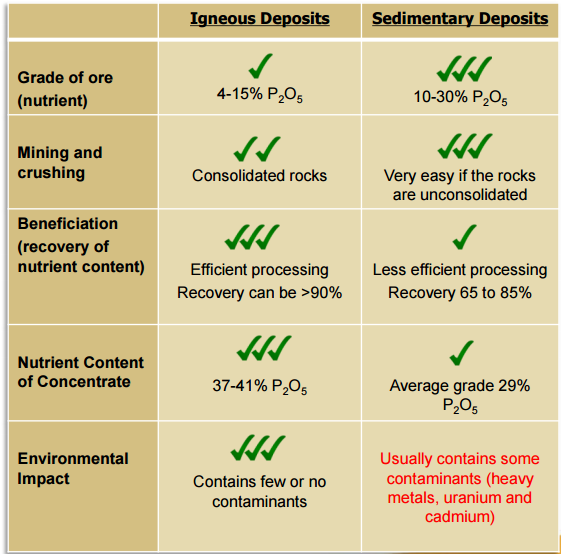

Phosphate rock can come from two types of geologic deposits: Sedimentary or Igneous.

You'll remember from middle school that:

Sedimentary rocks are formed by the deposition of material at the Earth's surface and within bodies of water. Before being deposited, sediment was formed by weathering and erosion in a source area, and then transported to the place of deposition by water, wind, ice, mass movement, or glaciers. These are called agents of denudation.

Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava.

Over 90% of global phosphate comes from sedimentary rock. Less than 10% comes from igneous rock.

These are not equal in quality. Sedimentary rocks contain higher-grade ore. But recoveries and the final concentration of Phosphorous Pentoxide (P2O5) are higher with igneous ore. The most important distinction between the two is the presence of contaminates. Because of the way many sedimentary deposits are formed, they contain trace amounts of heavy metals, uranium, and cadmium. As such, many phosphates derived from sedimentary rocks are not ideally suited to be used in food industries.

If I had a giant phosphate deposit, I'd want it to be igneous.

Macro Recap

The world needs tonnes of phosphate — some 200 million per year and growing. Most of this (70%) comes from the Middle East. It's a critical element in food production as fertilizer, but also in many other industries. New mine capacity expected to come online by 2023 doesn't exactly give an investor warm fuzzies:

Saudi Arabia, 10 Mt/y

Morocco, 9 Mt/y

China, 9 Mt/y (exports are restricted)

Russia, 3 Mt/y

Peru, 3 Mt/y

Brazil, 2 Mt/y

Production in Tunisia is down from 8 Mt/y to 2.5 Mt/y since the Arab Spring. Russia exports the highest grade (39%) rock, but is under economic sanctions. Syria's civil war has led to a 58% drop in production from 2012 to 2013, and is likely not producing any at the present time. U.S. phosphate production is expected to decrease by more than 25 Mt/y in the next 15 years. It currently produces around 30 Mt/y and consumes it all. The U.S. is also the world's leading importer of phosphate rock.

Where will the quality phosphate rock of the future come from? And how can we profit from it?

Arianne Phosphate (TSX-V: DAN)(OTC: DRRSF)

In that list just above of where new mine supply is going to come from, I omitted Canada. It would fall just above Russia and just below China with 3 million tonnes of new supply expected to come online annually by 2023. That will likely all be produced by one company: Arianne Phosphate.